On Learning (and Not Learning) from Bernie Sanders

Bernie Sanders restored economic populism to the heart of American progressive politics, but unfortunately, some on the left seem determined not to learn from his example.

By Jared Abbott

In search of the longer-term silver linings of Bernie Sanders’s failed 2020 bid for the Democratic Presidential nomination, historian Matt Karp mused that “by 2032, today’s Bernie voters under fifty will likely represent a majority, and certainly a plurality, within the party electorate,” and, he implied, may therefore have the electoral strength to deliver the resounding victory for democratic socialism that eluded Bernie. Yet, even if that were true, Karp wondered, “What sort of left will be there to greet them? Will it be a thoroughly post-Sanders progressive movement, whose priorities are defined by social media discourse, billionaire-funded activist NGOs, and a friendly working relationship with the corporate Democratic Party?”

Five years on, we have enough distance from 2020 to offer some tentative answers to this question. Progressives have made clear organizational and electoral gains in the past five years—enough to reasonably conclude the American Left is stronger today than it has been in many decades. Somewhat paradoxically, however, this strength was achieved to a large degree by forgetting rather than taking to heart the key lessons of Sanders’s two presidential bids. As a result, unless the Left undertakes a serious course correction, its post-2020 gains will become increasingly Pyrrhic.

What Sanders Achieved

Bernie Sanders’s most significant political achievement between 2016 and 2020 was to restore economic populism to the heart of American progressive politics. His candidacies marked the first meaningful assault on decades of neoliberal orthodoxy from within the Democratic Party. Sanders not only proposed a range of transformative economic policies to help millions of workers dig out of the wreckage of mass layoffs, disintegrating communities, and the collateral “deaths of despair.” He also named enemies, framed politics as a struggle between the many and the few, and reintroduced class conflict as a central axis of political life.

Sanders’s relentless focus on corporate power, inequality, and the erosion of working-class living standards revived an older political language long absent from mainstream Democratic discourse. The effect of Sanders’s campaigns was not merely symbolic—they reshaped the Democratic Party’s ideological terrain. This shift was notable not only during the 2020 presidential primaries, where economic policies that had once been considered fringe—like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal—were debated as serious policy proposals, but also carried over into the Biden administration, where Sanders’s influence was evident in both personnel and policy.

While the Biden administration backed away from the most ambitious elements of the Sanders platform and suffered from missteps in messaging, scope, and implementation, it nevertheless marked a decisive turn away from the technocratic neoliberalism of Biden’s Democratic presidential predecessors. Legislation such as the American Rescue Plan, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act reflected a new willingness to embrace expansive public investment, support for labor, and industrial policy that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier.

Public opinion also shifted in meaningful ways thanks to Sanders. While establishing direct causality is challenging, the Sanders campaigns clearly helped to reshape political common sense. Americans’ approval of labor unions rose steadily after Sanders’s 2016 campaign, reaching its highest level since 1965 by 2021, and proposals like Medicare for All and a jobs guarantee—long marginalized in elite circles—garnered substantial majorities in many polls. My own analysis of Voter Study Group panel data comparing the attitudes of the same voters between 2011 and 2017 shows that voters who supported Sanders in 2016 became more supportive of universal healthcare the following year than they were before 2016, suggesting a lasting attitudinal effect tied to a core plank of the Sanders campaign.

Sanders’s populism cut across traditional political and demographic boundaries, attracting voters who might otherwise fall outside the Democratic fold. For example, according to my analysis of data from the American National Election Study (ANES), 12% of Sanders supporters in 2016 identified as independents, compared to just 8% of Democratic primary voters overall. His campaigns also mobilized key constituencies that many Democratic candidates have struggled to engage, particularly young voters and Latinos. In 2020, over 20% of Sanders support came from Latinos, compared to just 13% of the Democratic primary electorate. His advantage among younger voters was even more pronounced: in 2016, 43% of Sanderistas were under 35, compared to 28% of Democratic primary voters.

There is also suggestive evidence that Sanders may have been able to keep at least some Trump-curious voters in the Democratic tent. John Sides estimated that 6 to 12 percent of Sanders supporters eventually voted for Donald Trump. Even if many of those voters would have abandoned Sanders for Trump in the general election, the Vermont Senator’s appeal to these cross-pressured or disaffected Republicans suggests that he may have been uniquely positioned to keep them in the Democratic tent in a way other candidates could not. His cross-ideological and cross-demographic appeal gave rise to a theory of change: that a majoritarian coalition built on bread-and-butter economic issues could overcome traditional cleavages in American politics.

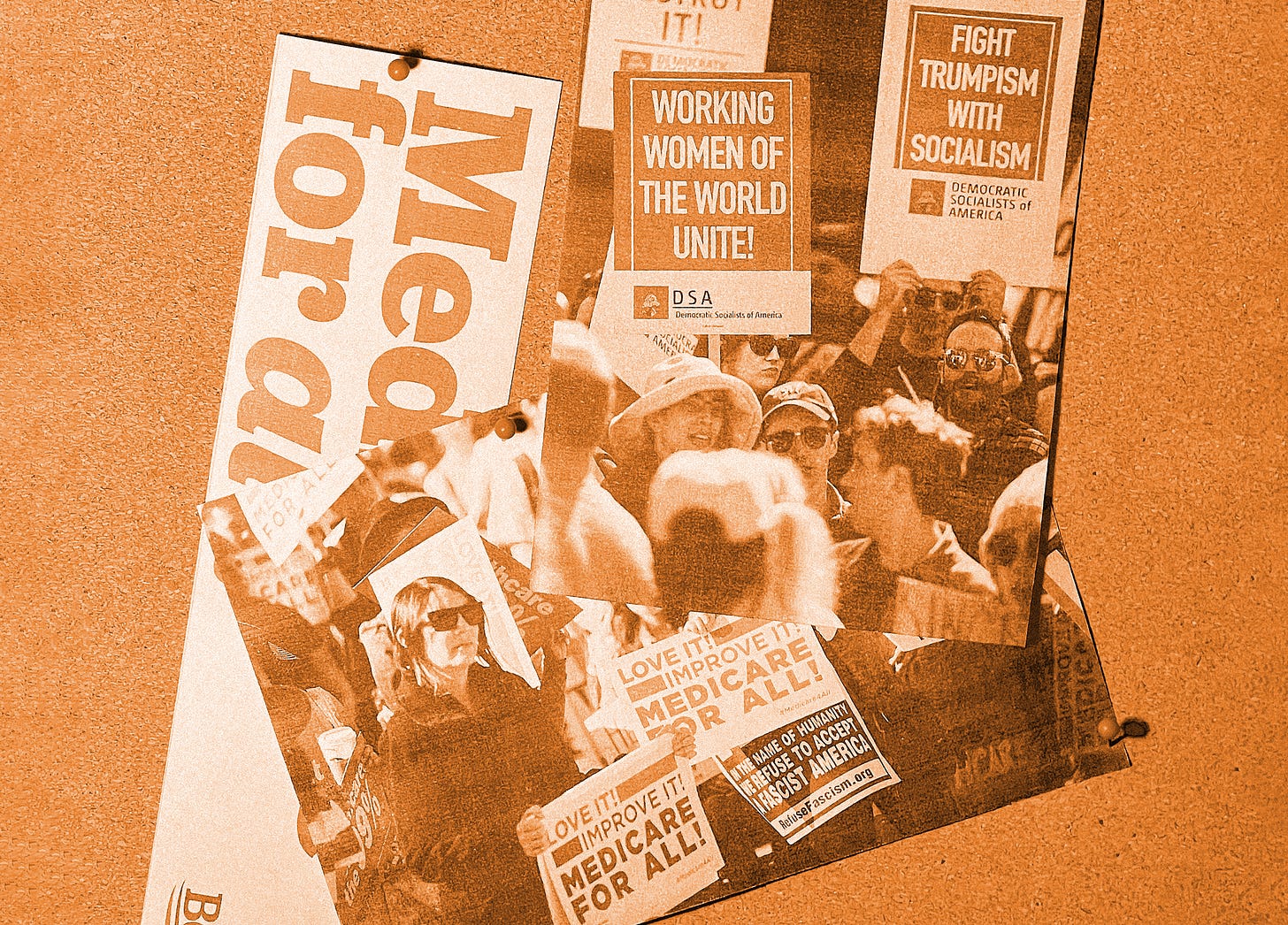

A final potent—though, as I discuss below, ambivalent—legacy of Sanders’s campaigns is the rebirth of the US Left and revitalization of rank-and-file labor organizing. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the trajectory of the Democratic Socialists of America, who grew from less than 10,000 members in 2015 to nearly 95,000 by 2021, thanks in part to Sanders-inspired momentum—though likely due even more importantly to Trump’s 2016 victory which swelled the ranks of virtually all progressive activist organizations. On the electoral front, groups like Justice Democrats emerged directly from the Sanders 2016 campaign, helping elect candidates who have become part of “the Squad” in Congress. Sanders’s campaigns also gave ordinary people who had never been politically engaged a tangible way to participate in movement-building. His campaigns turned voters into volunteers, Twitter followers into canvassers, and canvassers into candidates.

More broadly, well over 200 socialists have been elected to office across the country since 2016, the vast majority to town and city councils, but many also as city and county executives and state legislators—representing a 100-year high water mark for electoral socialism in the United States. While these candidates had diverse reasons for throwing their hat in the ring, many, like New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, directly cited Sanders as a key inspiration: “I had been working twelve hours a day,” she recounted. “I did not have health insurance. I was being paid less than a living wage… The only reason I thought running for office was even possible for me was because of his [Sanders’s] example.”

Sanders likewise had a measurable impact on labor organizing. According to a survey conducted by Eric Blanc, over a third of workers engaged in union drives since 2022 cited Sanders as a key influence in their decision to participate in workplace organizing efforts. More generally, a recent uptick in strike activity, increased numbers of workers organized through NLRB elections, and a host of new grassroots organizing efforts around the country since Sanders’s historically pro-union campaigns are also at least in part a legacy of his efforts.

What Sanders Did Not Achieve

A major shortcoming of Sanders’s political strategy is the failure to build electoral infrastructure for working-class power beyond beating establishment Democrats in safe blue seats. Apart from a handful of notable exceptions like Dan Osborn in Nebraska and Rebecca Cooke in Wisconsin, few candidates cultivated or endorsed by Sanders or post-Sanders organizations like Our Revolution and Justice Democrats have mounted serious efforts to replicate Sanders’s populist appeal beyond left-leaning urban strongholds or college towns, and vanishingly few have succeeded. In fact, not a single Our Revolution, Sunrise, or Justice Democrats-endorsed Congressional candidate has flipped a Republican-held seat over the past four election cycles.

Additionally, Sanders did not foster a pipeline of viable candidates in swing districts or a nationally competitive successor who could build on his message. While Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is widely recognized as a torchbearer of Sanders’s politics and has been a strong advocate of economic populism, she has positioned herself on many cultural and social issues in ways that may limit her appeal among more conservative or working-class constituencies. A recent Economist/YouGov poll, for example, found that just 34% of Americans had a favorable view of the four-term Congresswoman from New York’s 14th district—including just 12% of 2024 Trump voters, 31% of ideological moderates, and 27% of independents. To be fair, these numbers are slightly more positive than support for Democratic Congressional leaders Chuck Schumer and Hakeem Jeffries—who came in at 29% overall favorability in the Economist/YouGov survey—but they do not bode well as an indicator of national viability.

Sanders also failed to deliver on one of his campaigns’ most ambitious claims: that they could bring new voters into the political process. According to my analysis of panel data—comparing the same voters’ responses over time—from the Voter Study Group, only about 2.5% of those who didn’t vote in 2012 turned out to support Sanders in the 2016 Democratic primary. Sanders’s base, while large and enthusiastic, was composed primarily of habitual voters—especially younger and more progressive ones. In 2020, Sanders again failed to deliver a turnout revolution.My analysis of panel data from the ANES between 2016 and 2020 suggests that 2016 nonvoters made up a slightly larger share of Joe Biden’s 2020 primary supporters than Sanders’s (6.6% vs. 5.3%, respectively).

Finally, it is possible that Sanders’s choice to broaden his political message in 2020 blunted his appeal among working-class voters. While Sanders’s 2016 campaign was sharply framed around class struggle and economic justice, in 2020 he campaigned on a much wider array of detailed policy comments on comprehensive immigration reform, racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and environmental justice. This shift in focus—reflecting both the evolving political terrain of the Democratic Party and an effort to respond to demands from key constituencies within the progressive base—contributed to a strategic ambiguity around Sanders’s core appeal—one that may have made it harder to consolidate or expand support among working-class voters, particularly those ambivalent about or indifferent to progressive social positions.

It is difficult to measure the impact of Sanders’ message shift on voters’ attitudes. Survey data from the ANES suggest Sanders’s support among working-class voters did not change substantially between 2016 and 2020 when measured by income or education. This could either indicate that Sanders’s 2020 messaging pivot did not hurt his chances among working-class voters or that it set an unnecessarily low ceiling on the size of his coalition. In any case, the 2020 campaign may have inadvertently reinforced a view among some progressive populists that, so long as candidates center economic issues, they need not worry when their positions diverge dramatically from voters’ views on divisive social and cultural issues. It is important to note that the jury is still out on the extent to and the conditions under which prioritizing more extreme cultural positions hurts progressive economic populists. That said, the “yes and” perspective of many on the left—who believe that campaigning on unpopular social and cultural positions does not hurt progressives as long as their first priority is economic populism—risks underestimating the challenge of building broad working-class coalitions in electorally competitive settings—particularly if the class message is overshadowed by signals that alienate more culturally moderate voters.

What the Left Has (and Hasn’t) Learned

There is no doubt that progressives have learned positive lessons from Sanders’s campaigns. One of the most important—which has been absorbed by at least part of the Left—is that economic populism is politically potent. Candidates like Marie Gluesenkamp Perez in Washington, Gabe Vasquez in New Mexico, and Dan Osborn in Nebraska have won or run credible campaigns in highly competitive races rooted in Sanders-style rhetoric. These figures embrace class-forward messaging while couching their positions on cultural and social issues in ways that resonate with the values of their working-class constituents—a sign that Sanders’s core insight is filtering into broader strategy.

Moreover, organizations like the Rural Urban Bridge Initiative and More Perfect Union have worked to translate economic populism into practical narratives that can travel outside progressive enclaves. Likewise, new research efforts have been launched by groups like the Center for Working-Class Politics that have shown the potency of economic populist campaigning to win back these voters.

Sanders’s call to rebuild a stronger and more militant labor movement has been widely taken up across the Left. The 2018–2019 wave of teacher strikes—what Eric Blanc calls the “Red State Revolt”—showed the potential for militant labor action even in deeply conservative states. Many of the strike leaders were DSA members or democratic socialists; many more drew inspiration from the resurgence of class politics Sanders helped ignite. This spirit has since spread across sectors: the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC), a DSA-United Electrical Workers partnership, has supported hundreds of worker-led campaigns; the NewsGuild has trained rank-and-file journalists to unionize their own newsrooms; and workers at Amazon, Starbucks, and REI have built shop-floor committees, often without formal union backing.

Prepolitical Drift

The Sanders era also left behind some less constructive legacies. Perhaps most important has been a turn away from mass class-based politics aimed at forging a broad economic populist majoritarian coalition. In the absence of a coordinated movement to turn the energy of the Sanders campaign into lasting political power, many activists turned away from electoral politics entirely, doubling down on “prepolitical” activities as stand-ins for mass politics. While often worthy endeavors in themselves, when detached from or conceived as alternatives to a broader working-class movement, these activities can unwittingly cut against efforts to further the interests of the very poor and working-class communities they seek to uplift. Mutual aid projects like hosting brake light clinics and contributing to local food relief efforts—which became a nearly ubiquitous component of local DSA organizing after 2020—offered needed services but were typically framed as politically strategic “base-building” efforts or even revolutionary acts, rather than the largely apolitical community services that they were.

Similarly, progressive political education is often treated as a stand in for material change. Reading groups and employee/leadership development trainings have abounded in progressive and nonprofit spaces since 2020, but most have little connection to a broader strategic political vision. Instead, they substitute racially conscious rhetoric and interpersonal equity in the place of a strategic vision for shifting the balance of class power.

Even when progressive politics captured mass attention in the post-2020 period, it struggled to build durable political infrastructure—particularly the kind needed to tap into the deep well of economic populism that Sanders so effectively brought to the surface. Black Lives Matter dramatically raised public consciousness and shifted the national discourse toward a greater focus on racial inequality. Still, without lasting organization geared toward building class power, even the most impressive mass protests risk producing fragmentation, symbolic politics, or absorption into elite-friendly prepolitical domains.

Workplace Organizing Without Political Strategy

For all its symbolic and moral momentum, the new wave of Sanders-inspired worker organizing we have seen in recent years has so far yielded limited material advances in the broader balance of class power.

Indeed, the scale of organizing remains far below what would be needed to reverse labor’s long-term decline. US union density fell to a record low of 9.9% in 2024. Despite the uptick in energy since 2020, even the most active recent year—2023—saw fewer than 100,000 workers successfully unionized through NLRB elections. To return to the level of union density seen in the early 1980s, the labor movement would need to organize roughly 1.6 million new members per percentage point of density regained, as Benjamin Fong, Michael McQuarrie, and Maria Esch have shown. At current rates, that level of growth is not remotely within reach.

Without a parallel political strategy—one that removes structural barriers to organizing and elevates working-class issues through a growing bench of pro-labor economic populists like Bernie Sanders—even the most inspiring local victories risk remaining fragmented and difficult to defend or expand beyond isolated cases. This lack of coordination undermines labor’s ability to shape legislative agendas, push back against a hostile legal and regulatory environment, or, like Sanders in 2016 and 2020, use electoral participation as a means of raising working-class consciousness in a context where there are precious few other opportunities for doing so on a mass scale.

Purity Over Politics

One of the most important yet insufficiently internalized lessons of Bernie Sanders’s disciplined economic populist campaigns (particularly in 2016) is the need to meet working-class voters where they are—not where progressives would prefer them to be. Rather than rallying a majority around an agenda that materially benefits working people across race and geography, too many progressives continue to speak in a moral register that presumes agreement rather than building it.

This points to a failed lesson of the Sanders era: winning large majorities in favor of transformative economic reforms is not only more practical for delivering lasting gains, it’s also our best hope for halting the advance of right-wing authoritarianism. Without rebuilding trust among working-class voters in purple and red districts, progressives cannot hope to flip control of Congress, or meaningfully address the economic dislocation and political alienation that have fueled Trumpism. This isn’t about pandering, but rather making sure the core economic message can cut through to voters who aren’t with progressives on all the issues. As US Representative Sarah McBride, the first openly transgender member of Congress wisely put it, as progressives we should certainly “be ahead of public opinion, but we have to be within arm’s reach.” That means offering voters an olive branch, not a moral line in the sand.

The line between meeting voters where they are and compromising on core values isn’t always obvious and needs to be navigated continuously. When in doubt, following Sanders’s example, progressives should err on the side of humility and solidarity—delivering our message in ways that persuade rather than alienate. Only then can we build the kind of working-class coalition capable of turning back the tide of right-wing authoritarianism and delivering the economic transformation Sanders set in motion.

Relearning Politics

Sanders offered an important model for how the Left can build power through the political arena and use it to strengthen the hand of workers and labor on the shopfloor and in our communities, creating a mutually reinforcing virtuous cycle. That model remains incomplete. The question now is whether the movement he inspired will learn the right lessons.

If we have any hope of building a social-democratic future in the United States, progressives must build on the positive legacies of Sanders’s campaigns. That means moving away from the “prepolitical,” refocusing on formal politics and organized labor, and investing in community organizing aimed at rebuilding the lost infrastructure of working-class politics across American communities. It means building alliances—even uncomfortable ones—and contesting for power at every level in the red and purple districts we need to forge durable majorities.

The alternative is stasis at best and full-throated right-wing authoritarianism at worst. Sanders showed what is possible. The next generation of left leaders must finish what he started.

Jared Abbott is the Director of the Center for Working-Class Politics.